Asking “how to study in med school” likely conjures up images of all-nighters and endless sacrifice. Terms like “high yield,” “brute force,” and “firehose” are common. However, studying in med school doesn’t have to be an exercise in self-flagellation. Instead, it can be enriching, the foundation to a fulfilling career, and, dare I say, fun.

Learning how to study in med school is simple, but not easy. You need to:

- Use the best study techniques most of the time

- Study the most relevant material at the right depth

- Never forget what you learn in the most efficient manner

If that sounds too good to be true, it’s not. To understand the principles of effective studying in med school is simple. However, implementing them is challenging. Decades of our own baggage make effective change difficult. Our desire to follow our peers in our attempt to not fall behind also hampers us. However, students who successfully adopt these techniques will find success.

In this article, I will discuss a simple approach to master how to study in med school. It works whether your goal is to honor your classes, rock the Boards, or be an excellent physician.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Best Techniques for Mastery vs. Better Than the Placebo

We’ve all wasted time doing things where the results weren’t worth the effort we put in. For example, would you do 100,000 push-ups to lose only 1 pound? Or would you read an entire textbook to get one extra point on a test?

Many times, the results aren’t proportional to our efforts. However, we often don’t know in advance what will result from our actions. For example, when we set out to do 100,000 push-ups, we may be trying to exercise. We’ve heard that physical exertion is good for us. We want to lose weight. So is one push-up is better than none, then why not go to the extreme? No pain, no gain, right?

Except that this isn’t the right approach at all. We may want to lose weight, and it may be true that specific exercises may help us get there. It might be better than reading a book about exercise. In medical parlance, it may be better than the placebo, i.e., reading the book.

However, besting a placebo doesn’t mean that exercise is the BEST way to lose weight. (In fact, it turns out that going to the gym may not be the best way to lose weight).

Instead of asking what can bring us ANY results, why not ask what would give us the BEST results? In other words, the fact that something HAS utility doesn’t tell us HOW useful it is.

For example, you may have heard that mnemonics are “scientifically proven.” Or that summarizing something in our notes has been shown to improve retention. Those are both true statements. In other words, they really are better than the placebo. However, just saying they’re better than nothing doesn’t mean we should base our entire studying around them.

It turns out things like mnemonics, and many note-taking techniques are of “low” utility. They’re not useless. However, the outcomes are not proportional to the effort. There are better ways to use your day.

Use the Best Techniques Most of the Time

Study techniques that are only better than placebo are like opening a beer bottle with your teeth. It might be better than using your fingernails, but it doesn’t make it the best. Or advisable.

Instead of asking what is better than nothing, let’s ask what the BEST techniques are. The things with the most substantial evidence, and the highest effect size. I don’t care if I can memorize a list 50% faster if it won’t help me on an important exam or help patients.

I want the techniques that are the most effective and that apply to the broadest contexts.

In an insightful review article, the authors summarize decades of educational research. Instead of asking what is better than nothing, they rank various techniques to find what is best. Their criteria include:

- Ease of implementation

- Range of student characteristics

- Efficacy across a broad range of tasks

- How well they’ve performed when implemented in the real world

In other words, they scrutinized not only what works sometimes. They compared what works the best in most contexts. Specifically, they looked at:

- Summarization: Writing summaries (of various lengths) of to-be-learned texts

- Highlighting/underlining: Marking potentially important portions of to-be-learned materials while reading

- Keyword mnemonic: Using keywords and mental imagery to associate verbal materials

- Imagery for text: Attempting to form mental images of text materials while reading or listening

- Rereading: Restudying text material again after an initial reading

- Elaborative interrogation: Generating an explanation for why an explicitly stated fact or concept is true

- Self-explanation: Explaining how new information is related to known information, or explaining steps taken during problem solving

- Interleaved practice: Implementing a schedule of practice that mixes different kinds of problems, or a schedule of study that mixes different kinds of material, within a single study session

- Practice testing: Self-testing or taking practice tests over to-be-learned material

- Distributed practice: Implementing a schedule of practice that spreads out study activities over time

What do you notice about these techniques? You may have tried many – if not all – of them.

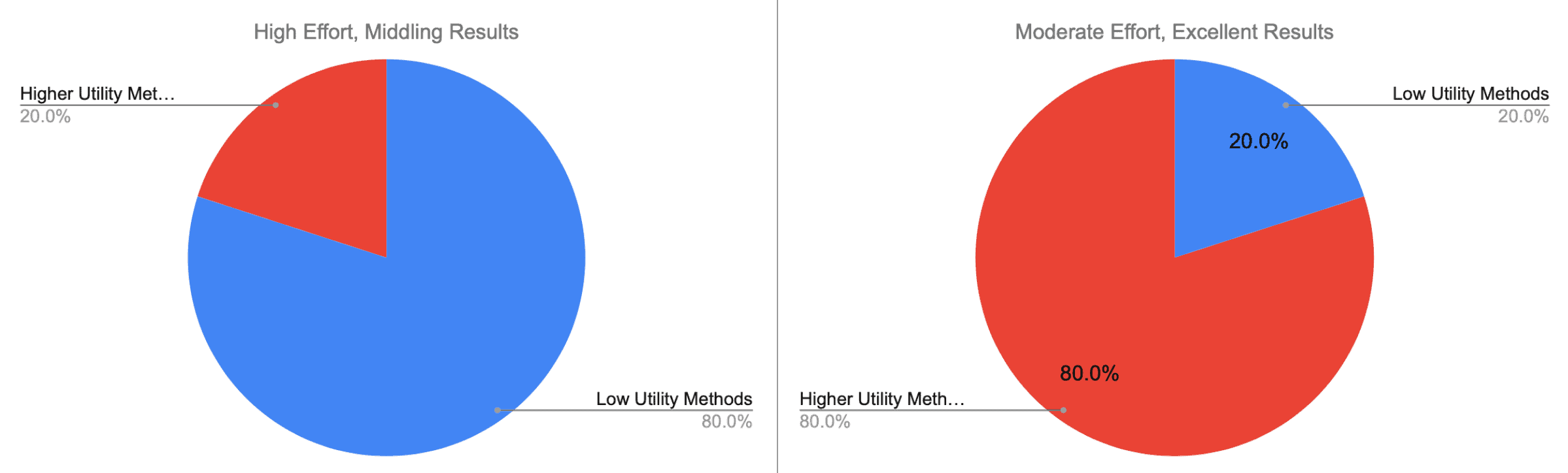

Here’s a summary of their findings, showing which they deemed the most and least useful:

Evidence-Based Techniques to Maximize Learning

| Technique | Description | Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Summarization | Writing summaries (of various lengths) of to-be-learned texts | Low |

| Highlighting/underlining | Marking potentially important portions of to-be-learned materials while reading | Low |

| Keyword mnemonic | Using keywords and mental imagery to associate verbal materials | Low |

| Imagery for text | Attempting to form mental images of text materials while reading or listening | Low |

| Rereading | Restudying text material again after an initial reading | Low |

| Elaborative interrogation | Generating an explanation for why an explicitly stated fact or concept is true | Moderate |

| Self-explanation | Explaining how new information is related to known information, or explaining steps taken during problem solving | Moderate |

| Interleaved practice | Implementing a schedule of practice that mixes different kinds of problems, or a schedule of study that mixes different kinds of material, within a single study session | Moderate |

| Practice testing | Self-testing or taking practice tests over to-be-learned material | High |

| Distributed practice | Implementing a schedule of practice that spreads out study activities over time | High |

Low Utility Techniques Are Familiar to Most Med Students

One thing that struck me was how often I used the low utility techniques when I started med school. I had tomes of summarization-type notes and highlighted lectures from my first year. I gobbled up mnemonics like it was my job. I had heard Anki cards were important – so I started memorizing facts from First Aid. And I thought I was such a good student for making time to re-read old material/notes.

I’m not alone. You, too, likely notice a lot of your day is consumed by low utility techniques. And it may be working! Like many med students, I overcame my inefficiency by diligence and more sacrifices.

In other words, I spent most of my day on low-utility studying. However, as a consequence of my low efficiency, I had to sacrifice more time. My results were ok, maybe slightly above average.

Study More Hours vs. Make Each Hour More Effective

Realizing that I was going to burn out if I continued on the low-utility treadmill, I resolved to change. Specifically, instead of studying more hours, I wanted to make each hour of studying more effective.

In other words, I needed to use higher-utility study techniques the majority of my day.

The key isn’t to study more hours. Rather, it’s for each hour to have maximum impact.

I stopped highlighting and used mnemonics only as a last resort. My notes became more sparse, and I increased my use of Anki. I spent much more time making connections between topics I was learning and things I already knew.

Instead of re-watching course videos, I started making better Anki cards and using active rather than passive learning. These cards took advantage of the high/moderate-utility categories:

- Self-explanation – relating new topics to things I’d already studied

- Elaborative interrogation – asking, and explaining “why?” for everything I learned

- Practice testing – testing myself daily on the cards I made

- Distributed practice – using the spaced repetition algorithm

My results gradually improved, to the point that I consistently scored in the top 10% of my Stanford class. This despite:

- Sleeping more,

- Taking on more extracurriculars, like research and TAing the max that Stanford allows

- Ignoring large swaths of our professors’ PowerPoint slides (more on breadth later)

Part 2: Right Scope / Breadth

A unique challenge to medical school is knowing WHAT to study. Before med school, you probably had enough time to learn everything and learn it well. At the least, you had enough time to cram everything needed the night before the test.

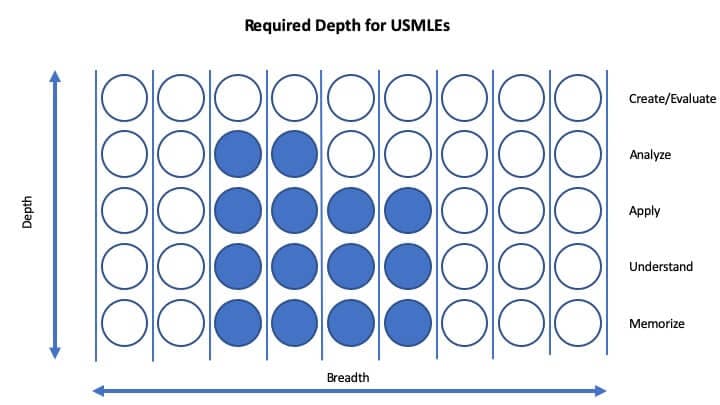

In med school, the volume of information is too much. We have a finite amount of time. We have an unlimited amount of material we could learn. This leads to a fundamental dilemma: how to allot our time to achieve the right:

- Depth – how much to master a given topic, and

- Breadth – which subjects to cover

This leads to following one of two extremes:

- The Ph.D. Approach

- Jack of All Trades, Master of None

The Ph.D. Approach: Too Much Depth, Not Enough Breadth

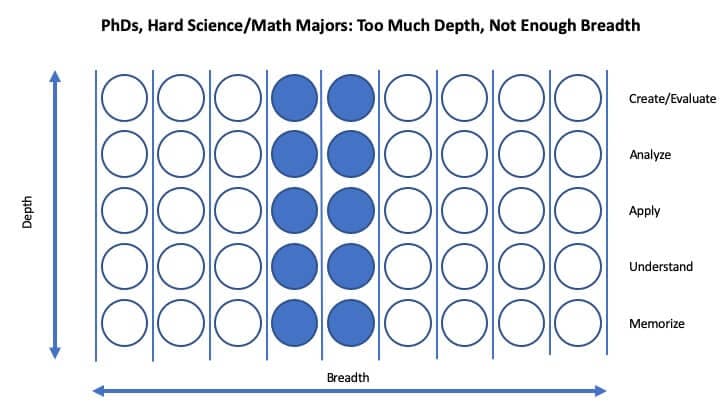

Some students have a natural affinity for learning things in depth. It’s pleasurable, and it’s familiar to them. This is especially true if they studied engineering, math, or physical sciences, or have a Ph.D. I call this the “PhD Approach”:

Spend so much time learning everything you can about a topic until you become an expert

It works exceptionally well in Ph.D./physical science type situations. In these fields, your goal is to apply/use these concepts. Plus, the volume is never the issue. Conceptual understanding is always more complicated.

In med school, though, the Ph.D. Approach fails because the volume is too much. You just don’t have the time to consult primary literature for everything you learn.

The diagram of the Ph.D. Approach would look something like this:

Studying in med school is not like earning a PhD

When the Ph.D. approach fails, many succumb to the most common way to study in med school.

Jack of All Trades, Master of None

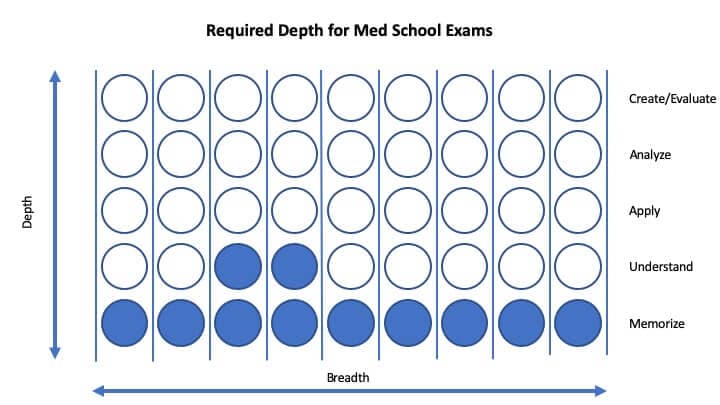

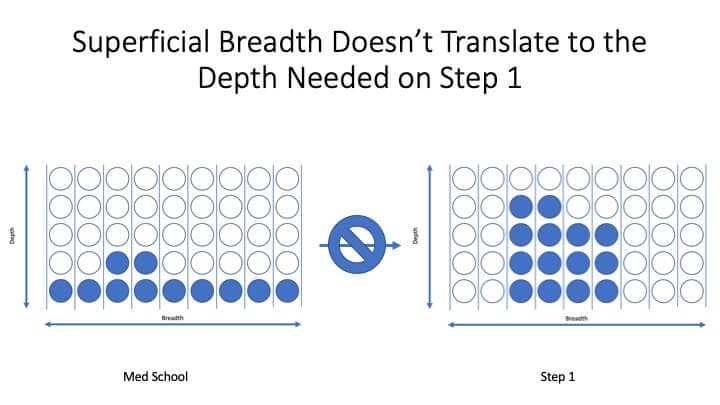

Because of the immense volume of material, many students resort to cramming. They indiscriminately learn every detail presented from class. However, because of the intense amount, they obtain only very superficial depth.

To do well on med school exams, you don’t need a lot of depth. You don’t have to understand the material well, most of the time. Many med schools test you on random details the professor deemed necessary. So the “Jack of All Trades, Master of None” approach works, at least for med school exams.

It’s tempting to memorize everything without obtaining much depth for med school exams

However, to do well on Step 1, the rules are different. Rather than having the breadth of most med school midterms, Step 1 requires much more depth. Question writers, rather than testing superficial facts, probe the application of concepts. Thus, to do well, you have to master what you’re learning.

However, effective USMLE studying requires adequate depth. (And not quite as much breadth as many med school exams).

This creates a dilemma. On the one hand, you’re going to feel the need to memorize everything from class. You’ll miss questions because you didn’t remember the fourth line of the second slide. You’ll feel panic well up.

So most med students focus only on their med school tests. But what do they sacrifice? Depth. Because they’re trying to remember every detail, they can’t learn anything well.

And this lack of depth will come back to haunt them. Remember, even though you can cram for med school tests, you can’t cram for Step 1. You need mastery of the material – you need depth!

It is extremely difficult to transition from memorizing to mastery during your dedicated study

The Solution: Restrict Your Scope, Ask Why, and Make Connections

So what should you do?

You need to restrict your scope. It’s suicide to try and cover everything equally. Why? Because by covering “everything,” you’ll lack depth in anything.

Instead, you need to attain depth in the most critical subjects. How do you know what is most important? By focusing on mastering the material in First Aid, and supplementing it with:

- Explanations of “why?”

- Connections between topics

And by making connections within and between topics, you can do more in less time.

But What About My Class Grades?

Studying the right material well – rather than “covering everything” – will likely lead to better grades, even if that’s not your focus. However, how important are class grades anyway?

The upshot of a survey on residency program directors: class grades aren’t as important as you’d think. Unlike clerkship grades, preclinical grades are of minimal importance for residency interviews. Here are the most important criteria residencies consider for granting interviews:

| Factor | Percent Citing Factor | Average Rating of Importance |

|---|---|---|

| USMLE Step 1/COMLEX Level 1 score | 94% | 4.1 |

| Letters of recommendation in the specialty | 86% | 4.2 |

| Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE/Dean's Letter) | 81% | 4 |

| USMLE Step 2 CK/COMLEX Level 2 CE score | 80% | 4 |

| Personal Statement | 78% | 3.7 |

| Grades in required clerkships | 76% | 4.1 |

| Any failed attempt in USMLE/COMLEX | 70% | 4.5 |

| Class ranking/quartile | 70% | 3.9 |

| Perceived commitment to specialty | 69% | 4.3 |

| Personal prior knowledge of the applicant | 68% | 4.2 |

| Grades in clerkship in desired specialty | 67% | 4.3 |

| Audition elective/rotation within your department | 64% | 4.2 |

| Evidence of professionalism and ethics | 64% | 4.5 |

| Leadership qualities | 61% | 4.1 |

| Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) membership | 60% | 3.9 |

| Perceived interest in program | 59% | 4.1 |

| Other life experience | 58% | 3.8 |

| Passing USMLE Step 2 CS/COMLEX Level 2 PE | 56% | 4.2 |

| Volunteer/extracurricular experiences | 54% | 3.8 |

| Consistency of grades | 54% | 4 |

| Lack of gaps in medical education | 53% | 4 |

| Awards or special honors in clinical clerkships | 52% | 3.6 |

| Graduate of highly‐regarded U.S. medical school | 50% | 3.8 |

| Gold Humanism Honor Society (GHHS) membership | 47% | 3.8 |

| Awards or special honors in clerkship in desired specialty | 46% | 3.8 |

| Demonstrated involvement and interest in research | 41% | 3.7 |

| Visa status (IMG only) | 40% | 4.1 |

| Applicant was flagged with Match violation by the NRMP | 37% | 4.8 |

| Away rotation in your specialty at another institution | 26% | 3.8 |

| Interest in academic career | 24% | 3.8 |

| Fluency in language spoken by your patient population | 24% | 3.7 |

| Awards or special honors in basic sciences | 22% | 3.3 |

| USMLE/COMLEX Step 3 score | 16% | 3.4 |

What do you notice? No preclinical grades! Why? I’d imagine it is in part because most schools are pass-fail. It would seem odd to penalize the few that have grades. So most residencies don’t seem to care. Even in the MSPE – which is quite important – preclinical grades are barely mentioned, if at all. For example, at Stanford, our MSPE had something generic like, “Alec earned a ‘pass’ in all of his preclinical courses.” That’s it! Two years, summarized with a simple, “pass.”

If you are at a rare school in which your preclinical grades are reported in the MSPE, you might ask how they are reported. However, since most schools are pass-fail, programs won’t know if you scored a 70 or a 95. They’re all still a pass!

What do residency programs care about a great deal? Your Step 1 score.

(To read Study for Classes or Step 1? Here’s How to Rock Both, click here)

Part 3: Never Forgetting What You’ve Learned

Remember one thing:

The worst studying is the studying you have to repeat

It’s a colossal waste of time to have to re-learn something. Let’s say you studied diabetes once in your biochemistry block. If you forget it, you’ll have to re-learn it once you get to endocrinology. And cardiology. And nephrology.

Once you get to Step 1, maybe you’ve learned it enough times that you’ll remember it. But probably not. Most students need another “pass” or two – at least – when they get to Boards.

Re-learning topics is a waste of time that sacrifices sleep, sanity, and Boards scores. Instead, once you’ve used the right techniques, and have the proper scope, make sure you never forget it.

But how do you make sure you never forget something? By using spaced repetition and making high-quality Anki cards. Note that by “use Anki” I don’t mean “memorize a list of facts like all your friends.” It’s tempting to think that spending minimal time on making Anki cards will save you time in the long-run. However, that is penny wise, but pound foolish.

Learn how to make Anki cards that make integrations and explain why. In other words, cards that use as many of the higher-utility techniques as possible.

To learn more, read Med School Anki: Make (or Find) USMLE-Crushing Flashcards.

Low Utility Study Habits Aren’t Useless. That’s the Problem.

One of the hardest lessons I’ve had to learn was not to do something that works. On the surface, that might sound absurd. For example, I used to take super extensive notes. When I did this, my grades would improve. Doesn’t that mean I should just take more and more notes?

No, I shouldn’t take more and more extensive notes just because it works.

Why? Because there are many more effective ways to study in med school.

Why didn’t I immediately change to new techniques?

Because note-taking still WORKS. It may not work great. However, if you do it enough, you can compensate for it. And like a gambler at the slot machines, we get just enough success to keep us going.

You may be wondering: if taking notes is low utility, what should I do? Should I never take another note?

While taking tons of notes may have worked in college, it quickly became untenable for me in med school. Instead, you might try taking what would otherwise go into notes and putting them into Anki cards. This will allow you to test yourself on it actively.

Concluding Thoughts: How to Study in Med School

Studying in med school is like taking a (very) long hike. On a long hike, you need to:

- Move at a good pace (using the right study techniques)

- Choose the right direction (choosing which materials to study wisely)

- Not re-trace your steps (never have to re-learn something you’ve learned)

Your chances of success require all three conditions. Apply the right techniques to the wrong material, and you’ll be disappointed. Study the right things well, but forget everything, and you’ll waste lots of time.

For further reading to help you on your way, I recommend the following:

- Motivation 101: Can You Learn To Love Med School? (Part 1)

- UWorld + First Aid: 4 Keys to Mastery (#4 Bumped Me to 270 from 236)

- Med School Anki: Make (or Find) USMLE-Crushing Flashcards

- Study for Classes or Step 1? Here’s How to Rock Both.

- The Secret to Scoring 250/260+ You Can Learn Right Now: Question Interpretation

- How Are USMLE Questions Written? 9 Open Secrets for Impressive Boards Scores

How much of your day is low utility studying? Why do you think we continue to do things that are only marginally helpful? Let us know in the comments!

Hi Alec! I use your Anki cards and read your blog frequently, and both have been a huge help in my studying, so thanks! I’m an MS2 and am wondering what you would recommend to do with a really short dedicated. My school allots ~5 weeks of dedicated if we take Step1 during the week recommended. 7.5 weeks is the absolute max we could have if we take the exam the weekend before clerkship orientation starts (which is a hard deadline, and the school discourages waiting that long). I’m only just beginning to realize that 5 weeks seems a bit short compared to the amount of time most people take for dedicated. (Is it?) Do you recommend any changes in strategy based on this shortened amount of time?