Every medical student has roughly the same approach to studying for USMLEs. It goes something like this:

- Find someone who scored well on the test

- Ask them precisely what they did

- Try and copy what they did

It makes total sense! It’s also what I tried to do. However, it’s also wrong for three primary reasons.

Table of Contents

1) You Take Only Part of the Plan (Usually the Dedicated Study)

Ever wonder what someone who scores 250+ on a USMLE does during dedicated study? They did tons of questions (possibly hundreds per day). And their scores soared like rockets.

You may think, then, that all YOU have to do is to do tons and tons of questions, and your scores will skyrocket. However, you’d be wrong.

Why? Because their dedicated study is only a (tiny) piece of their entire studying. Know what they likely did in the years BEFORE dedicated study? They:

- Mastered a lot of material

- Made a lot of integrations across topics

- Learned things deeply, and didn’t memorize minutiae

However, if you only look at what they did during the 3 months before their exam, you’d think it was just the questions!

Looking Only at the End of the Plan is Dangerous

How absurd is it to ask only what someone successful did during dedicated? Let’s say I want to be an NBA player. Let’s say I ask people who were drafted in the NBA what they did in the months leading up to playing in the NBA. They might tell me, “all I did was play pick-up games.” Or maybe it would be, “I did a lot of conditioning exercises.” Who knows? (I’m clearly not a basketball player).

However, would copying LeBron’s pre-game routine make me play like LeBron? Of course not. In addition to genetic gifts, these players have spent decades honing their craft. Obviously, asking them only what they did over 3 months won’t help me play in the NBA. In fact, it may make it even less likely, since what helps a pro is different from what helps a beginner.

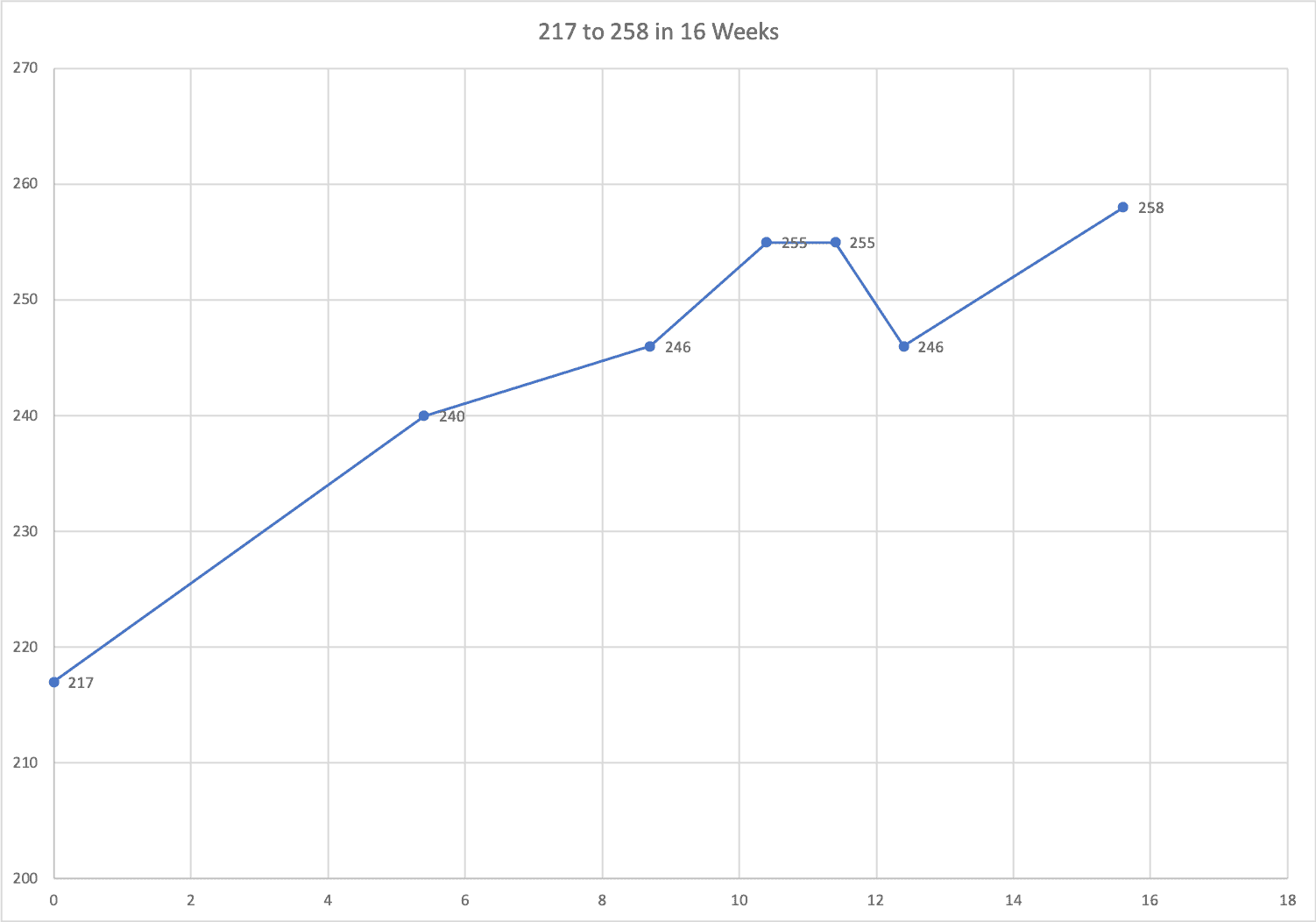

Here’s an example from a student I worked with starting his first year of med school. Here are his scores.

This student scored 258. He also started dedicated study at 246. Should you do lots of QBank questions just like he did?

| Week | Score | Form |

| 0 | 217 | NBME 12 |

| 5.4 | 240 | CBSE (School) |

| 8.7 | 246 | NBME 13 |

| 10.4 | 255 | NBME 15 |

| 11.4 | 255 | NBME 16 |

| 12.4 | 246 | NBME 17 |

| 15.6 | 258 | Step 1 |

Note that his starting score at the start of dedicated was 246. He’d already completed the Kaplan QBank.

What did he do? He did a lot of questions! So, of course, you should do a lot of questions, right? No, of course not, unless you are starting with a similarly solid foundation.

2) The Frankenstein Plan

We at Yousmle follow one path to mastery over memorization. However, many successful students have found their own ways to gain an in-depth understanding.

A wrong approach, however, is to ask ten students what they did and try and copy all ten. Each will have had subtly different methods. Maybe one student really liked annotating First Aid. And another started using this shiny new QBank.

The worst is how med students try to convince each other to follow their own plan. There seems to be a deep-seated need to be part of a group. Students will “recruit” their friends to their program. Everyone feels better, at least for a time, because everyone else is doing it!

What you end up with is what I call the “Frankenstein Plan.” You know, the one that has one piece from one plan, and another from a different one. It’s like this amalgamation of all of the collective “wisdom” of medical students.

The problem with this is simple. Time is finite. The more you spend on one activity, the less you’ll have for another. Annotating First Aid may work in a particular context. It has no chance if you’re trying to do 100 other things.

The take-away? Choose only one approach, rather than trying to follow five strategies at once.

3) Silent Evidence

Have you ever noticed that what we know in theory is difficult to apply in practice? Like I may be excellent at spotting “rationalization” on a test, but unable to detect my own.

The same is true, unfortunately, with research biases. You know, those things that you memorized for your test. Today we’ll talk about “silent evidence,” a form of selection bias. In it, you look at only a subset of a population and make mistaken generalizations.

A great example comes from Nassim Taleb, in Black Swan. It goes something like this.

Let’s say you take a population of rats from New York City. The strength of the rats follows a normal distribution. Some rats are stronger, some are weaker, and the majority cluster around the mean.

Next, you put them in a large cage and subject the entire rats to escalating doses of radiation. First, the weakest rats die, say, the bottom 10%. As you increase the dose, though, more and more rats start to die. You stop only when 3% of the rats are surviving. Those rats are the most robust 3% of rats from the original population.

Now let’s say you put the surviving, previously irradiated rats through a battery of tests. You’d find, to your surprise, that the irradiated rats were STRONGER than any random sample of NYC rats!

Did the radiation make the rats stronger? Of course not. All you did was create a lot of “silent evidence.” In other words, you killed off the weaker rats and selected only for the strongest rats.

“Proof” for Med Student Study Plans is Replete with Silent Evidence

Now replace “rats” with “medical students” and “radiation” with “memorize UFAP.” (Or *shudder* any of the plethora of memorization-heavy flashcards floating around). You’ll find a very similar dynamic at work.

If we subjected a heterogeneous population of medical students to UFAP, what would we find? If they all tried to memorize and mindlessly do questions, the students would get weaker. Their brains would atrophy. They’d become bored, disillusioned, and start to wonder why they went to medical school.

Instead of dying off, lower-performing students would simply feel inadequate. “What’s wrong with me?” they’d wonder. They’d grow silent in class and wonder why they couldn’t do well. Their peers always seem to know the answer!

We Only Hear from the Successful Ones

Even though everyone used the same methods, only the ones who did best will trumpet it.

“Yes, UFAP! Do lots of questions!” they’ll proclaim.

The high scorers will be feted, sought out by junior students. Those in the 10% of scorers will be on panels, bellowing how everyone they know who scored 250+ “just did questions.” And they would be right! What they don’t mention, however, is that a lot of the people who scored BELOW average also did lots of questions.

Those students with less stellar scores are the silent majority. They won’t go around saying how doing a lot of questions caused them to do poorly. (Although they would be justified in doing so!). Instead, they will be going through rounds of agonizing self-blame. They’ll wonder what they did wrong, how they “did what we were supposed to do,” but still ended up in disappointment.

But the astute observer will recognize that the STUDENTS weren’t the problem. The strategy they followed actually hurt them! Yet they don’t know that. It’s like the weaker rats blaming themselves for dying from the radiation. It doesn’t make sense. However, because of the phenomenon of silent evidence, students will still blame themselves.

To Find the Best Technique, Seek Out Silent Evidence

Just because someone did well on the USMLEs doesn’t prove that their technique was the best. It’s like the strongest rats claiming that being irradiated MADE them strong. In any group of students, there will be variations in ability/prior knowledge. Selecting the top students doesn’t mean that it was their technique that got them there.

So, if you wanted to know what was indeed the best approach, what should you do? You need to seek out the silent evidence. In other words, instead of only asking people who did well, seek the perspective of those who didn’t as well. This is infinitely harder than finding people who scored well. People who scored below average will not want to share their results. However, they will give you incredibly valuable advice.

I have tutored students for more than a decade on the USMLEs. I’ve seen all manner of outcomes. Some students started with high scores and wanted to do even better. Many others were struggling and trying to figure out what was wrong.

The approach of the 250+ scorers is EXACTLY what low-scoring students are doing. In other words, they repeat UWorld again and again. They re-read First Aid and annotate it. They’ll watch and re-watch the same videos. Why? Because everyone “knows” that’s what everyone who scored 250+ did!

Successful Students Did Lots of Questions. But So Did Many Who Failed.

However, the flaw in the reasoning is obvious. Yes, everyone who scored 250+ on USMLEs indeed did lots of questions during dedicated. However, it’s also true that many people who FAIL the USMLEs took the same approach! It proves nothing.

So what are you, a deep thinker, to do? You realize the flaws in others’ reasoning and deliberately seek out silent evidence. You not only want to find what top scorers did. You ALSO want to seek their systematic differences from low-scorers.

Could it merely be that it’s all innate? Is everyone doomed to do the same thing, and only the geniuses will do well?

No! While abilities may play some role, my observation is that a different dynamic is in play. High scorers are, in fact, different. Even better, this difference is something that can be learned!

However, it’s not in what they were doing during dedicated study that set them apart. In virtually every case, high scorers have a deep understanding of the material. Just like many low-scorers, they did lots of questions. However, unlike low-scorers, they always ask, “why?” They won’t cram. Instead, they will spend extra time developing a deeper understanding of concepts.

Concluding Thoughts

How do you know I’m not just pulling your chain? What if mastering material is just another form of irradiation, meant to weaken you?

Like any good science experiment, you need a testable, refutable hypothesis. You need not only to be able to prove it right but also to prove it wrong if the facts are inconsistent with the theory.

My hypothesis? Low-scorers were memorizers and crammers, while high-scorers mastered the material.

The proof is empiric and is easy to verify. Instead of asking only 250+ scorers what they did, commit to querying a VARIETY of people. Ask them how much of their time was devoted to questions during dedicated. You’ll find that in most cases, there wasn’t a big difference. Then ask them what they did in the years BEFORE dedicated study. Things like:

- What was your first NBME score of dedicated studying? (I.e. did they start with a high score?)

- How much did your score improve using the dedicated study method you used?

- What was different about your approach?

- How strong was your baseline going into your dedicated studying?

- What do you think was the most important part of how you studied before you started dedicated studying?

- Anything else that can help you determine what they did differently than their silent-evidence peers

So the next time you want to find the best approach, remember:

Seek the silent evidence

Hello Alec, I’m a 4th year student from Mexico, I‘ve started using Anki and literally changed my life.

I have a question for you, i have been having trouble knowing when I should create the cards. Shall I read the topic first? Shall I create the cards on class (time efficient). Shall I study first from the text book and then creating my cards? What do you think is the best way to do this?

In Mexico at the beginning of third year you start with clinical rotations and you return to school to have theoretical lectures on the rotation you are doing (1- month long) but these lectures topics are not synced with the clinical rotation topics, so actually I have to read one topic daily for my rotations and another one for my theoretical classes, how would you establish the process of creating and reviewing cards, taking into account that I need to know the topic before the next day’s rotation.

Thank you in advance!